Introduction

The history of human freedom is, in practice, a long sequence of acts of disobedience. No fundamental right was ever generously granted by kings, dictators, or bureaucrats. Everything we have achieved as free individuals was born from resistance—and often from the refusal to obey.

That’s why, in times of censorship, surveillance, and increasingly arbitrary laws, speaking about civil disobedience may sound, to some, like a crime or senseless rebellion. But nothing could be further from the truth. Disobedience can be a legitimate, ethical, and necessary act.

This text is a straightforward guide: the bare minimum you need to understand what civil disobedience is, where it comes from, when it is justified, and how it can be applied. Because one day, knowing this could be the line between dignity and submission.

Definition, Justification, and Principles

Civil disobedience is the public, deliberate, and non-violent refusal to comply with certain laws, orders, or demands from the State, when such laws are deemed unjust or illegitimate. It is not vandalism, nor armed revolution—but rather rational and moral resistance.

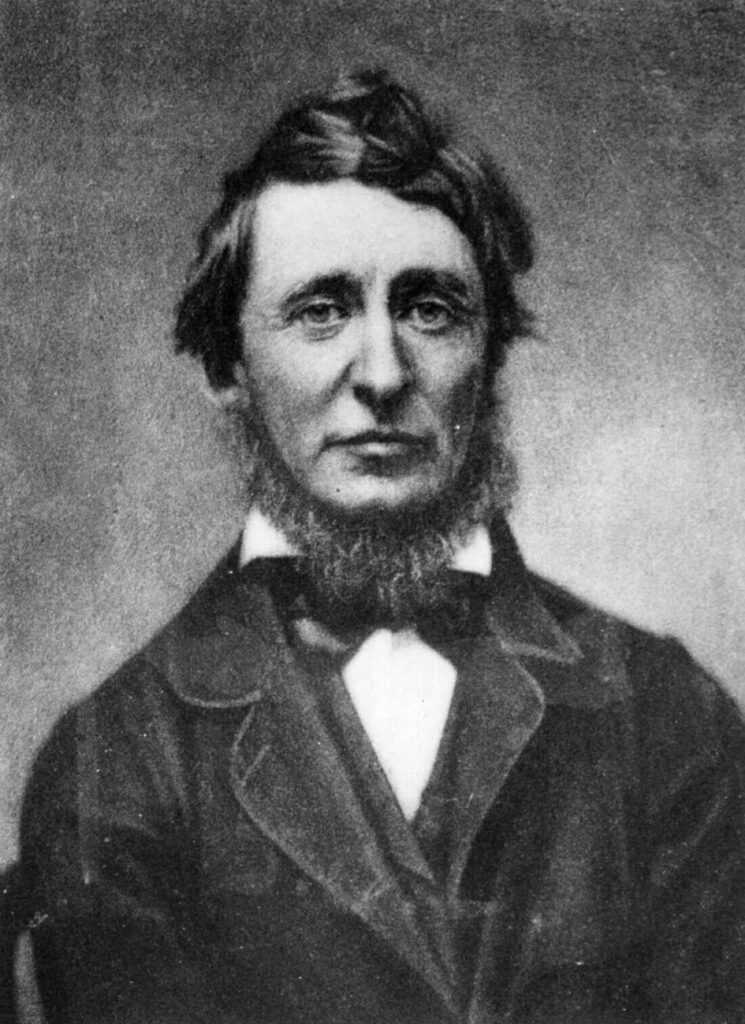

The term was popularized by 19th-century American philosopher Henry David Thoreau, who refused to pay taxes that would fund slavery and the war against Mexico. His stance became a milestone in Western political thought.

At its core, civil disobedience is based on a simple principle: State authority has limits. Citizens have a moral duty to resist rules that violate their conscience, their liberty, or the natural rights of any human being.

Disobedience is justified when the State abandons its duty to protect the common good and begins to operate as a tool of oppression. In such cases, obedience becomes complicity.

This does not mean that any disagreement with the law justifies disobedience. It should be reserved for situations of clear, systemic abuse with direct impact on fundamental freedoms.

In this context, disobedience becomes a form of protest—a message to the system, to society, and to History itself. It is the individual saying: “No. I will not take part in this.”

Key Thinkers of Civil Disobedience

Besides Thoreau, several other thinkers helped shape the concept and practice of civil disobedience. Among the most prominent are Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and John Rawls.

Gandhi adopted civil disobedience as a central tool in his struggle for India’s independence. His principle of satyagraha (truth-force) inspired millions and proved that peaceful resistance can be stronger than violence.

Martin Luther King Jr. applied the same principles during the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, confronting segregation laws through marches, protests, and a refusal to bow to legalized racial injustice.

John Rawls, a 20th-century political philosopher, argued that civil disobedience is a legitimate part of a healthy democracy. When institutions fail, disobedience acts as a corrective and a moral appeal to the public.

Other figures such as Hannah Arendt, Leo Tolstoy, and Étienne de La Boétie also wrote extensively about the legitimacy of resistance. They all reinforce one core idea: no social order should ever be placed above human dignity.

These thinkers show that civil disobedience is not individual whim, but a historical, ethical, and philosophical tool for defending freedom.

Civil Disobedience in Practice

Many historical episodes prove the power and nobility of civil disobedience. The Montgomery Bus Boycott in the United States, the Solidarity Movement in Poland, and even recent protests against vaccine passports in countries like France and Italy are all examples of contemporary resistance.

In Brazil, there are also examples. Farmers who resisted unjust expropriations or citizens who refused to comply with absurd mandates during the pandemic showed that resistance is not only legitimate—it is necessary.

Civil disobedience does not require violence, but it does require courage. Standing up to the State—even peacefully—often comes with a price: fines, imprisonment, persecution.

It is precisely because of this that, when done with moral awareness and a willingness to face the consequences, civil disobedience becomes a public testimony—not an empty rebellion.

In authoritarian regimes—or democracies in decay—civil disobedience is one of the last available forms of resistance before total servitude or civil war. History teaches us: when good people obey too much, evil governs in peace.

The Top 20 Questions and Answers About CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

1. What is civil disobedience?

Civil disobedience is the conscious, public, and usually peaceful act of refusing to comply with laws, orders, or mandates from the State when those rules are considered unjust, immoral, or unconstitutional. It is a legitimate form of protest used to draw attention to abuses of authority and to demand reform—as seen in the American Civil Rights Movement and anti-austerity protests across Europe.

2. Isn’t breaking the law a crime?

Legally, yes. But not everything that is legal is just. Civil disobedience is based on a higher standard—justice, ethics, and natural rights. An act can be unlawful, yet morally correct. Resisting segregation laws in the U.S. or opposing authoritarian regimes in Eastern Europe are prime historical examples.

3. What’s the difference between civil disobedience and ordinary disobedience?

Civil disobedience is driven by moral or political convictions and aims at social change. Ordinary disobedience is simply violating rules for personal convenience—like speeding to avoid traffic. The former seeks justice; the latter seeks self-interest.

4. Is civil disobedience always peaceful?

Traditionally, yes. Civil disobedience is distinguished from armed rebellion by its commitment to nonviolence. However, in some contexts—such as state overreach in Eastern Europe or aggressive police crackdowns in the U.S.—it may escalate into self-defense or physical resistance.

5. Who can practice civil disobedience?

Any conscious citizen. You don’t need to be a politician, activist, or leader. A lone student in Poland, a mother in the Netherlands, or a worker in Michigan—all can spark movements by refusing to comply with injustice.

6. What are the risks of civil disobedience?

They vary by regime. In open democracies like the U.S. or Germany, risks might include fines or arrest. In more authoritarian settings, such as Hungary, Belarus, or historically in Brazil, the risks may include censorship, persecution, or violence. Courage is essential.

7. When is it morally justified to disobey?

When obedience requires betrayal of one’s conscience, complicity in injustice, or denial of basic human rights. When following the law would mean supporting evil or violating one’s deepest ethical beliefs, civil disobedience is not just justified—it becomes a moral obligation.

8. Does civil disobedience actually work?

Yes. Landmark changes have been born from it: India’s independence, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of segregation in the U.S., and mass resistance to authoritarianism in Eastern Europe. When strategically executed, it is a powerful force for change.

9. Wouldn’t it be better to change laws through democratic processes?

Yes—when those processes are functional. But in countries like Belarus, Russia, or even in moments of democratic decay in the U.S. or Brazil, legal channels are often blocked or manipulated. In such cases, civil disobedience exposes institutional failure and mobilizes public conscience.

10. Doesn’t disobedience undermine the State?

It depends on the kind of State. A healthy democracy can withstand—and even grow from—civil disobedience. But authoritarian states fear dissent because they depend on blind compliance. Refusing to obey unjust laws doesn’t destroy the State—it forces it to be accountable.

11. Is civil disobedience the same as a boycott?

They are related. A boycott is a specific form of economic civil disobedience—like refusing to buy from companies involved in war or environmental abuse. The Montgomery bus boycott in the U.S. and the anti-apartheid boycotts in Europe are classic examples.

12. Can I engage in civil disobedience alone?

Yes. Movements often start with one voice. Rosa Parks in the U.S., Jan Palach in Czechoslovakia, or Edward Snowden’s defiance—individuals who acted alone and changed global discourse. Collective action is powerful, but individual courage ignites it.

13. Is disobeying a court order a form of civil disobedience?

It can be—when the order contradicts fundamental rights or justice. Civil rights leaders in the U.S. and political dissidents in Europe have at times defied court orders for moral reasons. However, it’s a serious legal step and requires ethical clarity and a readiness to face consequences.

14. What role does the media play in civil disobedience?

In free societies, media can amplify the message of civil disobedience—as seen during the George Floyd protests or the Yellow Vests in France. But in manipulated systems, media can become a propaganda tool to smear dissent. Controlling the narrative is vital.

15. What are the ethical boundaries of civil disobedience?

Civil disobedience must respect others’ rights—especially life, liberty, and property. You can’t justify injustice in the name of justice. The power of disobedience lies in its moral high ground, which must be fiercely protected.

16. Do religions support civil disobedience?

Many do. Christian, Jewish, and even Islamic traditions recognize that when earthly laws contradict divine or moral law, obedience to God takes precedence. As the Bible states: “We must obey God rather than men.” (Acts 5:29)

17. Is civil disobedience common in the U.S. and Europe today?

Yes. In the U.S., examples include resistance to COVID mandates, Second Amendment sanctuary movements, and mass protests against abortion laws. In Europe, recent waves of farmers’ protests in the Netherlands, resistance to digital IDs, and opposition to overregulation all involve forms of civil disobedience.

18. Is civil disobedience the same as anarchy?

No. Anarchy rejects all government. Civil disobedience accepts legitimate authority but opposes tyranny. It’s not a denial of the State—it’s a defense of a just one.

19. Does the U.S. Constitution permit civil disobedience?

Not explicitly—but it protects freedoms of speech, assembly, religion, and conscience. When these are violated, civil disobedience becomes a justified response. Similar protections exist in European frameworks such as the European Convention on Human Rights.

20. What happens if everyone disobeys at once?

The system collapses—and that may be necessary if the system is deeply unjust. Mass noncompliance led to the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and major civil rights gains in the U.S. A society that knows when to say “no” is a society that knows how to resist tyranny.

What Would Happen If People Resisted State Overreach?

The answer is simple: the State would lose its power to abuse. All tyranny depends on the obedience of good people. When the good say “no,” the house of cards begins to fall.

If thousands of citizens refused to comply with unjust orders, the state apparatus would stop. If police officers, judges, civil servants, and ordinary workers said, “this is unacceptable,” there would be no force strong enough to sustain the oppression.

But fear paralyzes. Comfort numbs. Dependence on state benefits binds. That’s why those who disobey with moral awareness become examples, beacons, and seeds of a freer society.

To disobey is not to hate the country — it is to love it enough not to let it fall into ruin. It is to do what is right, even when the law says otherwise. It is to say, with your own life, that there are limits to any government’s power.

And maybe, if more people understand this, disobedience will no longer be necessary. Because rulers will think twice before crossing the line. After all, a people who know when to say “no” are the greatest terror of tyrants.

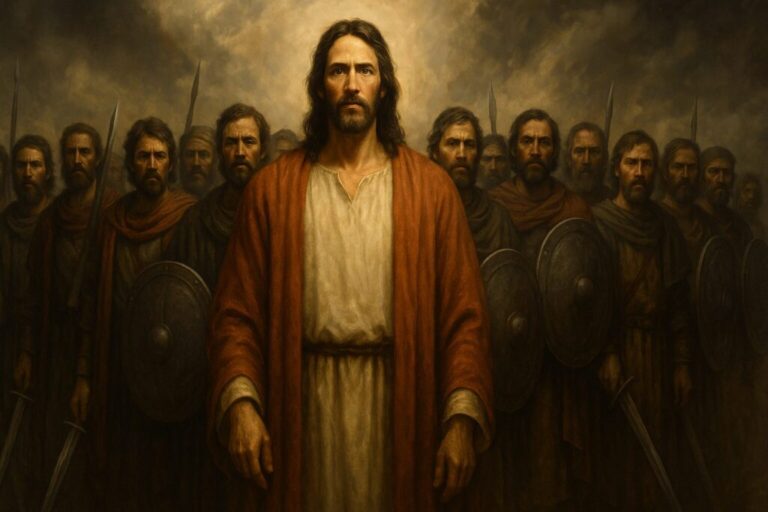

Extra Chapter: Jesus Christ, the Apostles, and Civil Disobedience in Their Time

Throughout history, many resistance movements have been inspired by the example of spiritual leaders. Jesus Christ and the apostles are among the greatest examples of obedience to God combined with disobedience to unjust human power. Although Christianity has long been associated with submission, an honest analysis of the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles reveals a more complex picture: a movement of deep and conscious civil disobedience.

Political and religious context of the time

Jesus and the apostles lived under the rule of the Roman Empire, a highly authoritarian regime that allowed some religious freedom to the Jews but harshly repressed any threat to its authority. At the same time, the Jewish religious system had become corrupted, becoming an accomplice to Roman power and oppressing the people with human traditions, rigid laws, and heavy spiritual burdens.

In this environment, both state and religious power demanded blind obedience and conformity. Any questioning of the status quo was quickly silenced with violence or exclusion. It was in this scenario that Jesus appeared, not as an armed revolutionary, but as someone who placed truth and justice above social and political conventions.

Jesus and the confrontation with the system

Jesus did not start a violent rebellion, but He openly challenged religious and civil authorities. He drove out money changers from the temple, called the religious leaders “whitewashed tombs,” denounced the system’s hypocrisy, and taught that true authority comes from God, not from men.

The episode of the tax to Caesar is revealing: when asked whether they should pay taxes to the emperor, Jesus replied, “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, and unto God what is God’s” (Matthew 22:21). This answer, often misinterpreted as support for the State, actually affirms that there are limits to civil authority — and that when Caesar demands what belongs to God (such as conscience or worship), he must be refused.

Jesus healed on the Sabbath, touched lepers, spoke with Samaritans, sat with tax collectors and prostitutes — all of these actions violated the prevailing social and religious norms, revealing a deep disregard for man-made impositions. He obeyed God’s law, but resisted the human traditions and rules that enslaved the people.

The apostles and the refusal of illegitimate authority

After the death and resurrection of Christ, the apostles carried on this legacy of conscious disobedience. Peter and John, when forbidden to preach, firmly replied: “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29). This is perhaps the clearest and most direct statement in the Bible about civil disobedience.

They were arrested, flogged, threatened — and continued preaching. They did not seek violent confrontation, but they did not bow to unjust prohibitions. They met secretly when needed, helped persecuted Christians, and often directly defied orders from both civil and religious authorities.

The apostle Paul, although he wrote about the importance of civil order (as in Romans 13), was himself imprisoned multiple times for preaching where it was prohibited, for refusing to be silent in the face of injustice, and for asserting his Roman citizenship to defend himself — showing that he recognized limits to the State’s power.

Disobedience, martyrdom, and conscience

All of the apostles, except John, were killed because of their faith. This did not happen by accident, but because they refused to obey orders from the State or religious leaders who commanded them to be silent. They were arrested, tortured, and murdered because they disobeyed out of fidelity to God.

The civil disobedience of the early Christians was neither reckless nor ideological. It was rooted in conscience, faith, and truth. It was a refusal to participate in a corrupt system, to deny Christ, or to put fear above their mission. Ultimately, it was a form of worship: to obey only what is just.

The legacy for Christians today

Today, many Christians have been conditioned to think that obeying the State is always a virtue. But the example of Jesus and the apostles shows otherwise: when the State demands what belongs to God — conscience, truth, freedom — it must be disobeyed.

Disobeying an unjust law is not rebellion against God, but faithfulness to Him. The early Christians knew this. They faced prisons, censorship, executions — but never yielded to authorities who tried to erase their faith and mission.

To follow Christ is, in many situations, an act of resistance. It is to say “no” to the world, to lies, to oppression. It is to remain faithful to the truth, even if it costs your freedom or your life. And as the Lord Himself said: “If anyone would come after Me, let him deny himself, take up his cross, and follow Me.” (Matthew 16:24)