The idea of the university is so embedded in modern life that we often forget its origins. Today, universities are usually seen as secular, government-funded, or privately owned institutions. But if we trace history back far enough, we discover that the roots of the modern university system lie firmly within the Catholic Church.

The word “university” itself comes from Latin. The expression universitas magistrorum et scholarium means “community of teachers and scholars.” It was not merely a building, but a corporate body of individuals united for the purpose of higher learning. This was a unique creation of medieval Christian Europe.

Before the rise of the universities, monasteries and cathedral schools were the primary centers of education in the West. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, literacy and scholarship nearly disappeared in many regions. Monks, however, preserved not only Scripture but also classical works of philosophy, law, and medicine. Without this foundation, the later development of universities would have been impossible.

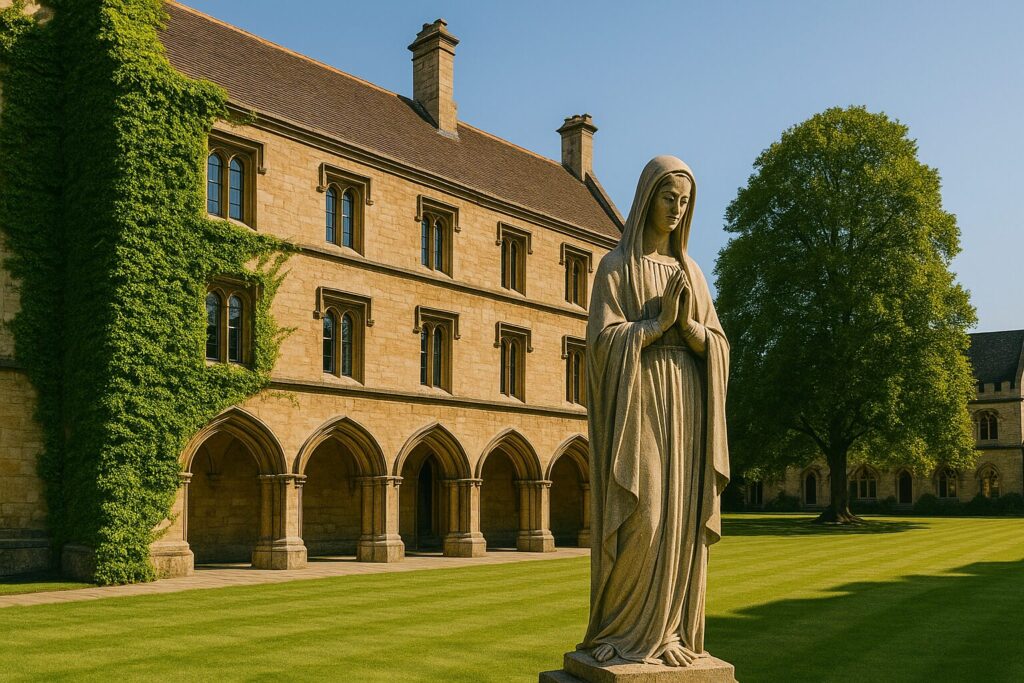

One of the first great examples was the University of Bologna, founded around 1088. Bologna specialized in the study of law—particularly Roman law and canon law—and quickly became a magnet for students across Europe. What made Bologna unique was its organization: students grouped themselves into “nations” according to their origin and even hired and paid their own teachers.

Meanwhile, in France, another center of learning was rising. The University of Paris, which emerged around 1150, grew directly out of the cathedral school of Notre-Dame. Paris became famous for its theological and philosophical debates, especially under figures such as Peter Abelard and Thomas Aquinas. Papal recognition granted the university autonomy, making it a model for other institutions.

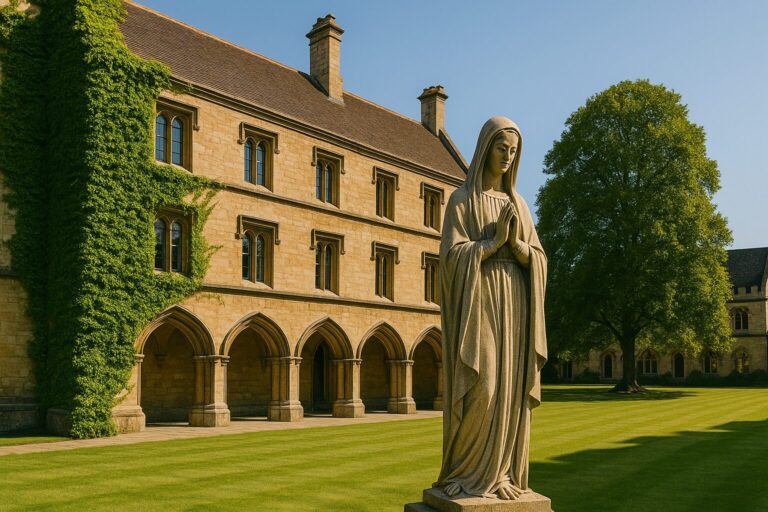

In England, the University of Oxford began developing in the late 12th century. Many of its scholars had studied in Paris, bringing back methods and traditions. Oxford soon rivaled Paris, and after conflicts with local authorities, some scholars left Oxford and founded the University of Cambridge, establishing another lasting center of Christian learning.

In Spain, the University of Salamanca, founded in 1134 and officially recognized in 1218, played a crucial role in shaping Iberian intellectual life. Like Paris and Bologna, Salamanca thrived under papal authority, producing theologians, lawyers, and philosophers who influenced both Spain and the wider Catholic world.

The papacy itself was central to this process. Through papal bulls, the Church granted universities privileges and protections. Pope Gregory IX’s bull Parens Scientiarum (1231) gave Paris independence from local authorities and affirmed the rights of its scholars. These papal charters set the template for universities across Europe.

The language of instruction was Latin, the common language of the Church. This allowed a German to study in Italy, a Spaniard in France, or an Englishman in Spain, without language barriers. The Church’s universality was mirrored in the universality of Latin.

Universities were typically organized into four faculties: Arts, Theology, Law, and Medicine. The Faculty of Arts taught the seven liberal arts—grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—as preparation for the higher faculties. Theology, the “queen of the sciences,” was the highest pursuit, deeply tied to the mission of the Church.

Degrees such as bachelor, master, and doctor also originated in this medieval Catholic context. They were essentially licenses to teach, granted by the authority of the Church. The system of examinations, disputations, and academic gowns still used today all stem from this period.

The scholastic method, championed by theologians like Thomas Aquinas, emphasized reason, dialectic, and systematic debate. Far from being “anti-science,” the Church fostered a culture of rational inquiry within the framework of faith. This intellectual tradition laid the groundwork for the scientific developments of later centuries.

It is important to note that universities were independent corporations, not directly controlled by local kings or princes. Their authority came from the Pope or the Emperor. This autonomy allowed them to flourish, sometimes even resisting secular pressure, and to develop their own identity as communities of scholars.

Over time, universities multiplied. By the 13th century, institutions had appeared in Naples, Padua, Montpellier, and Coimbra. Each specialized in different disciplines: law in Bologna, theology in Paris, medicine in Montpellier, and so on. But the Catholic stamp was visible in all of them.

The impact of these universities on Western civilization cannot be overstated. They produced not only theologians and priests but also lawyers, physicians, and administrators who shaped medieval society. Their graduates staffed courts, hospitals, and governments, spreading knowledge beyond the cloister.

Critics often claim that the Church opposed science. Yet the very existence of universities, created and protected by the Church, shows the opposite. It was in these institutions that medieval natural philosophy—the precursor of modern science—was cultivated. Figures like Roger Bacon, Albertus Magnus, and William of Ockham were all products of this system.

Even the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries owed much to the Catholic universities. Copernicus, for example, studied at the University of Bologna and the University of Padua, both steeped in Church tradition. Galileo himself was educated by the clergy.

The Church’s role in education also extended beyond Europe. With the Age of Exploration, Catholic missionaries founded universities in the Americas, such as the University of Santo Domingo (1538), the University of San Marcos in Lima (1551), and the University of Mexico (1551). These institutions spread the university model across the globe.

While modern universities have largely secularized, their DNA remains Catholic. The structure of faculties, degrees, academic freedom, and even the idea of a community of scholars come directly from medieval Catholic institutions.

This legacy is a reminder that the Church was not only a religious authority but also a cultural architect. By investing in education, preserving knowledge, and institutionalizing learning, the Catholic Church ensured that Europe would never lose touch with its intellectual heritage.

Of course, the Church’s influence was not without controversy. Universities sometimes clashed with bishops, kings, or even the Pope himself. Students rioted, professors challenged orthodoxy, and debates grew heated. Yet this tension itself reflected the vitality of the system the Church had created.

The rise of the university also had political consequences. Educated lawyers trained in canon and Roman law gave rulers new tools for governance. Administrators shaped by scholastic reasoning introduced a new level of rationality into medieval politics. In this sense, the Church indirectly fostered the rise of more sophisticated states.

Over the centuries, the relationship between universities and the Church evolved. During the Renaissance, humanism brought new subjects into the curriculum. Later, the Reformation and Enlightenment created conflicts and reforms. But even when universities distanced themselves from ecclesiastical control, they remained indebted to their Catholic roots.

Today, when one walks through the halls of Oxford, Salamanca, or Bologna, the medieval imprint is still visible. The cloisters, the Latin mottos, the gowns, and the ceremonies all echo the Catholic past. Without the Church, these institutions simply would not exist.

To study the history of universities is to study the history of the Catholic Church. The two are inseparable. Far from suppressing learning, the Church created the very structures that allowed it to flourish.

And so, the next time someone praises the modern university as a triumph of secular reason, it is worth remembering: the first universities were born in cathedrals, monasteries, and under the blessing of popes. The modern world owes its educational system to the Catholic Church.

TO CHRIST BE ALL GLORY.

References

Haskins, C. H. (1957). The Rise of Universities. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Huff, T. E. (2003). The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leff, G. (1968). Paris and Oxford Universities in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries: An Institutional and Intellectual History. New York, NY: Wiley.

Rashdall, H. (1987). The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages (Vols. 1–3, repr. ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Original work published 1895)

Rüegg, W. (Ed.). (1992). A History of the University in Europe. Volume I: Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Southern, R. W. (1995). Scholastic Humanism and the Unification of Europe: Foundations. Oxford: Blackwell.

Verger, J. (1992). Men of Learning in Europe at the End of the Middle Ages. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.